Venetian art, from a historical perspective, has a reputation for being bright, bold and dramatic. Many of the best Renaissance artists emerged from the palazzo filled lagoon, and helped push drama in to art to forge the Baroque. Yet the latest show at the brilliant Ashmolean Museum in Oxford starts by claiming that drawing has been written out of the art historical studies of Venice’s artists.

A bold claim, and one that seems to overlook the importance of the cities artistic legacy – it’s not that Venetians couldn’t draw, but perhaps were overshadowed by the extraordinary penmanship of the Florentines, Romans and Siennese – the likes of Da Vinci and Michelangelo are incredibly technical, wonderfully detailed and expertly modelled, while these, are not. It’s like saying the Romans couldn’t quarry marble – it’s a necessary skill in making the sculptures we know them for.

What the show tries to illustrate is that in Venice, a different type of drawing flourished. They are much more sketchy, fluid, and display motion. They are less interested in bulging anatomy, but more in the gaze of faces and the sweeping gestures of human interaction. To an art historian, this comparison is somewhat clear, yet to the wider public, seems harder to decipher and the lack of pointers from the curator leaves it confusing.

The drawings are emotionally charged and raw, yet no one would expect them not to be – there is little surprise throughout.

The show brings together 100 works from the collections of the Ashmolean archive, Christ Church Cambridge and the Uffizi to show how sensuous Venetian drawing was. Unfortunately the show lacks a certain amount of explanation to art historical context and drawing technique is rarely touched on – the exhibition feels slightly muddled and curation seems lost. However the works shine, giving a touching insight in to the thought process of the great artists Tititan, Bellini, Titoretto, Tipepolo and Canaletto.

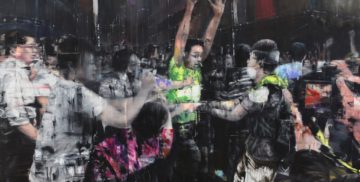

The British contemporary artist Jenny Saville was commissioned to create a series of works in response to the drawings that are exhibited in the final room. They seems disparate from the main show, and the dialogue isn’t clear – but the works do have a certain charm, especially the drawings of children (something oddly rarely featured in the main Venetian show). It also lacks the historical context and acknowledgement that the Venetian drawings are working studies never intended for display.

The concept however, of commissioning and displaying contemporary artists to create works in dialogue to old masters is something original and provoking – a path that more museums should walk. Perhaps if the two were curated together it would work better (The Rubens show at the Royal Academy did this brilliantly by selecting existing works that explored Baroque themes of drama and tension to show alongside the master’s paintings).

Titian to Canaletto, Drawing in Venice at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford brings together works not usually seen together as a well versed overview of the practising of drawing in Venice, yet none of the works are not on view normally in public institutions, and the exhibition leaves many questions unanswered about the importance of the pieces in a wider framework – yet as an aide to understand the creative process of the Venetian masters it makes for compelling viewing.