If you’ve ever been confused by the Bruegel family tree, you’re not alone. There are Pieters and Jans and Elders and Youngers, then further down the lineage, Kessels and Teniers become involved, and suddenly your head becomes foggy. But fear not, a new exhibition opening this week at the Holburne Museum in Bath is set to elucidate the whole situation – finally. It has been an age old source of great confusion for us all, especially considering there are such a vast number of works of art by the Flemish family in UK collections, and its a surprise nothing has been done to help explain the situation prior.

Thankfully, Bruegel – Defining a Dynasty opens with a family tree, so before you even get to lay your eyes on any art, you can get your head around the family: Pieter Bruegel the Elder had two sons, Pieter the Younger and Jan the Elder (who was actually the younger of the two). Pieter the Elder died when his sons were 1 and 4, and they learnt much of their father's accomplishments through his mother in law, their grandmother Mayken Verhulst who was a successful miniature painter in her day. Jan the Elder had two wives. The first wife, Isabella, had two children.

Jan the Younger (whose wife in turn had 11 children – many of them artists including Abraham Brueghel), and Paschasia Brueghel, whose child was Jan van Kessel the Elder. He in turn produced Jan van Kessel the Younger (and 12 others). Jan the Elder’s second wife Catharina gave birth to 8 children, one of whom, Anna, married the accomplished painter David Teniers. They in turn had a baby – the artist David Teniers III.

His great-grandfather was the original Pieter the Elder. Following? It only gets more complicated once you learn that throughout their lives they variously adopted and dropped the h in their surname depending on religious persuasions. So upon seeing this visual web, whilst making everything clearer, the situation is highlighted as much more complicated than one previously thought. Once you step inside however, something in the show clicks and you find yourself understanding the breakdown.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Visit to a Farmhouse, c.1620-30, Oil on panel, 36.5 x 49.4cm, © Holburne Museum. Photograph by Dan Brown.The exhibition begins with Pieter – the ‘Inventor Bruegel’. Through two small ink drawings, the show explains how Pieter was a new breed of artist making art for a new breed of middle class who wanted to emulate their upper class Flemish counterparts in taste (read; conspicuous consumption). Pieter set about making many drawings that could be printed and sold widely (although sadly few still exist).

Pieter’s inventiveness is further championed in a monumental painting generously loaned from the National Gallery of the Adoration of the Magi, which illustrates his move away from Renaissance ideals of form, proportion, colour and style. Gone are the temple settings, elongated characters and serene faces.

This adoration is straight from the barn with drunk peasants, dirty babies and weary kings who need a good bath after their journey. Its gritty realism is both simultaneously grimacing and hilarious – something that quickly becomes a theme throughout.

From here the show fragments in to the various branches of the dynasty. One such branch explores how Pieter the Edler’s sons learnt to replicate their fathers most in demand works through pin prick techniques, over time adding both personal touches and altering out of fashion elements in order to stay ahead of trends. Images become highly piled with metaphors and develop as visual allegories – one work in the show depicts over 90 proverbs amongst the action (each listed in the exhibition catalogue).

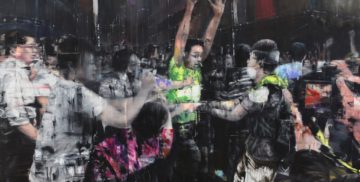

Looking at it is like watching a movie with every scene untangling at once before you as the characters bang their heads against brick walls and walk a mile in each others' shoes. It’s a wonderfully playful image that would have no doubt been a great dinner party conversation piece. As the years pass, the differences between the artists begin to show more and more – Pieter the Younger’s works become monumental religious scenes that place the viewer right in the action. Jan’s works on the other hand tend to become smaller, tighter compositions that focus on the wonders of landscapes, with figures second to the foliage and wildlife.

From here, each branch of the show disperses further. Still life painting emerged as a new fashionable genre from Italy, and never ones to miss a trick, the Bruegels’ were quick to dispatch a family member to Rome to learn the ropes and return to Flanders and begin taking orders.

These still life works soon turned in to decorative mounts for curio-cabinets depicting bugs and flowers with such realism they were often indistinguishable from the faithful article which they concealed. At the same time, painting on copper was invented and it offered a new method with which to create works that held such incredible vibrancy that they attained Jan the Younger the nickname of “Velvet Bruegel”.

Adam Naming the Animals, Circle of Roelandt Savery. Oil on Copper, 12.2 x 18.5cm, © Holburne Museum.What becomes quickly apparent whilst traversing this show is just how on the ball the dynasty were. Whilst they certainly were some of the most skilled and innovative artists of their day, they were also great marketeers. One work in the show, entitled The Rent Collectors is known to exist in at least 91 versions – and that’s just as an oil painting. These works were clearly mass produced for a newly emerging mass market – and suddenly during this show one realises the business savvy of this family.

This situation however, also throws a spanner in the direction of any curator – the varying size, quality and detail of these many editions make discerning which to show particularly tricky – especially when every gallery and auction house is keen to proclaim theirs the best. Several of the works in this show are also copies of their originals which are either now lost or in national collections world wide who clearly didn’t fancy loaning them.

Some of them aren't by members of the dynasty at all, but merely represent their stylistic qualities. For these reasons, the Bruegel masterpieces are thin on the ground – but not to discredit the Holburne, they still have assembled a particularly charming and well planned assemblage. What is particularly excellent though, is the curation which guides one through the time lime effortlessly, leaving a clear and succinct understanding of each family member’s role and importance in the story. And that’s no mean feat.

The real star of the show however, is Wedding Dance. A previously unattributed work held in the museum’s storage facility, which after careful restoration and x-raying was revealed to be an original Bruegel. This fairy-tale find makes it the only version of the Wedding Dance in a British public collection and the perfect cherry on top to the show. Y

ou can't help feel proud of the Holburne – the underdog gallery outside of London keen to display it's newly discovered masterpiece. One feels like congratulating them.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Wedding Dance in the Open Air, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Oil on panel, 36.6 x 49cm, ©Holburne Museum. Photography by Dominic Brown.The show feels incredibly tight knit considering it covers some 150 years of European painting in which so much changed, and through just 25 or so works. But nothing feels missed, lost, or spared.

Each picture treads carefully in to its neighbour and leads you on a journey of discovery that finally provides a layman’s explanation of this dynasty that everyone has for so long needed. Once one reaches the end it is hard to resist cycling the show again newly armed with the knowledge of how things would unfold for this family who went on to so fundamentally change the way northern European art would look, act and sell.