“Gradually but determinedly avoid being present at official or public ‘uptown’ functions or gatherings related to the ‘art world’ in order to pursue investigations of total personal and public revolution.”

With this personal and official statement, artist Lee Lozano not only withdraws from the artistic scene of 1960's New York, but from the art world at-large. It was 1969 and artists in the Big Apple were revolutionizing the way art was being made and consumed through a gradual and radical de-materialization of the object, a ‘minimalization’ of style and content and an analysis of the social and political implications of art and its institutions. By breaking the barriers between everyday life and art, young artists believed in the potential to make a change and to speak up about the global situation. This is the time when environmental, feminist, social and political matters make their way into artist’s practices. This is the time when the private and the political could no longer be separated.

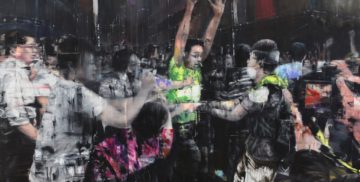

Lee Lozano, Forzar le máquina. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Mayo 2017. Photograph Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores. Archivo fotográfico del museo Nacional Reina Sofia.Lozano’s battle for uniting art and life was perhaps the most radical of all. The retrospective at Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid beautifully traces the changes and leit motifs of her short but intense artistic practice from 1961 to 1972. At the age of 31, Lenore Knaster moved to vibrant New York City after graduating from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1960.

She started working on an incredibly funny and clever series of erotic works that deal with the sexualisation and commodification of the body. A box with tits and penises on sale, a pair of breasts between a giant cross turning into a penis, male genitals ready to be incised by Lozano’s typewriting machine, all show her aggressive and very personal language which resonates also in her later minimal works of the second half of the 60s. Lozano’s interest in industrial or mechanical tools show her obsession for the erotic power and gender inflection of labour.

The shiny and sleek surface of a screw, its explosive potency almost bursting out of the two adjoined canvases, play out the visual similarity with male genitalia and the sexualisation of ‘hard’ labour. At the same time these sensual works comment the masculine style of minimalist art – think of Frank Stella, Robert Morris and Richard Serra – a genre dominated by male protagonists using an aggressive ‘virile’ language.

Lee Lozano, Ream, 1964. Oil on linen. 198.1 x 243.8 cm. Blanton Museum of Art. University of Texas, Austin. Donated by Mary and James A. Michener, 1968.While working out figurative and abstract forms through drawing and painting, Lozano explored her artistic thoughts, doubts and practice in writing. Her notebooks, exhibited in the galleries of the museum as if they were artworks, present plans for upcoming paintings alongside statements in capital letters acting as mini manifestoes and instructions for her daily life and work.

These instructions, carefully and orderly written with specific rules, conditions and sub-notes, are works of art in themselves. The most remarkable are those dealing with her concern on communication. Her most famous is perhaps Dialogue Piece consisting in inviting daily to her studio someone she knows or not knows for a chat. She then recorded in her notebook the date, place and topics of the conversation, however specificities of the chat such as thoughts, ideas and opinions remain private.

Many of her interlocutors were renowned artists, critics and writers of the New York art scene as she was well connected into the circle of upcoming artists and thinkers of the time. Interestingly in August 1971 she begun the Decide to Boycott Women Piece: by cutting all communication with women she hoped that, after a period of silence with her own gender, communication would improve. Inevitably all Pieces she set in motion meant that her everyday routine was imbued with art, or better a form of art that was de-materialized, all pervasive and radical. Feminist writer and art historian Lucy Lippard described her as “extraordinarily intense” and stated that she was the first one to fully put into practice the art-and-life ideal: “the kind of things other people did as art, she really did as life – and it took us a while to figure that out.”

Lee Lozano, Forzar le máquina. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Mayo 2017. Photograph Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores. Archivo fotográfico del museo Nacional Reina Sofia.In a search to purify, de-mystify and de-commodify her life and work, or perhaps just fed up with everything, her beliefs led her to the ultimate radical artwork: a complete withdrawal from the art world. Although her art lasts little more than a decade, her legacy is huge and still know critics, artists and historian are wondering if we will ever witness another artist as extraordinarily intense and radically revolutionary as Lee.

By Victoria De Zanche

Lee Lozano: Forzar la máquina at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 30 May 2017 – 25 September 2017

Are you following us on Instagram? Click here.