Having toiled for fifteen years as a director of commercials, J.C. Chandor made an impressive feature filmmaking debut in 2011 with Margin Call, a taut and timely drama concerning the onset of the 2008 financial collapse that earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Screenplay. He continued his role as fully adept writer/director with All Is Lost (2013), an astonishing – and slimly scripted – survival drama featuring Robert Redford adrift at sea and battling the elements.

With two impressive features behind him, Chandor returns with his third, A Most Violent Year (2014), a tense and historically evocative crime drama that’s both a gangster film for our time and a throbbing indictment of the crime, greed and deception this genre typically depicts and revels in.

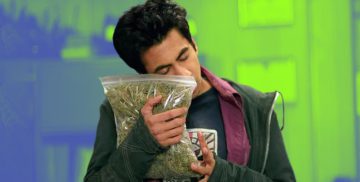

Taking place in New York in 1981, a year that is statistically the most dangerous in the city’s history, the film sees rising star Oscar Isaac playing Abel Morales, an ambitious Hispanic-American émigré who will stop at nothing to ensure the continued success and proliferation of his fuel company. Married to the equally ruthless Anna (Jessica Chastain) and father to two children, Abel’s ostensibly settled life is challenged, however, when forces beyond his control look to drastically unravel everything he’s strived to keep on the straight and narrow. “I like to own the things I use” is his going mantra.

Though he’s on the cusp of a lucrative business deal, Abel risks losing it all as he struggles to come to terms with the fact that he’s ingrained within an industry literally grounded on the notion that avoiding adaptation leads to damaging consequences.

Opening with shots that burrow deep within the underbelly of this supposedly besieged city, Chandor focuses on Abel running as both an establishing tool and metaphor for what’s to come. He is, in a sense, continuing to run through rings of self-preservation throughout the film, fuelled by ambition and the drive to triumph over his competitors. It’s these nefarious opponents who (he believes) have actively set out to damage his corporate reputation, something that culminates in a bracing, prolonged chase sequence rivalling The French Connection’s (1971) iconic scene in its sprawl and relentless pacing.

In an almost direct contrast to the physical and professional stagnation of the character that brought him to the spotlight – the titular wannabe folk star in the Coen Brother’s brilliant Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), Isaac is exceptional here as Abel, perfectly embodying the coiled anger of a man determined to keep his morals in check (rendering his surname all the more overtly ironic). It’s this ethical compass that’s challenged by underhanded circumstances enacted by both his business partner Andrew (an unrecognisable Albert Brooks) and his wife, whose Lady Macbeth-esque shadow follows Abel wherever he goes.

Isaac is ably accompanied here by Chastain, who imbues Anna – a stiletto nailed mob princess who challenges her husband’s passivity, all the while goading him to do and be better – with a deft combination of menace and devotion. Scenes of them verbally sparring with one another, only to then reconcile, are sensitive portrayals of a marriage built on lopsided foundations, not least when Anna exerts her control and reminds him that he’s the mere custodian of her family business.

In mining the tension in his protagonist’s part matrimonial, part business-partner relationship, Chandor uses this as a pertinent and synecdochic representation of the turf wars outside; making internal the external conflict, something boosted by Bradford Young’s muted cinematographic colour palette. As much a film about the cruel inevitability of the passing of time as it is about the pangs of maintaining supremacy in a treacherous climate, A Most Violent Year is a work of broiling intelligence from a first class filmmaker, one whose clear appreciation of cinema reigns supreme. “I’ve spent my whole life trying to not be a gangster,” Abel says at one point; an almost deliberate antithesis to the opening line in Scorsese’s masterpiece, Goodfellas, (1990), the likes of which Chandor’s latest effort comfortably stands besides.