The last of Wagner’s cycle of music dramas, Götterdämmerung, is a German translation of the Old Norse word Ragnarok, which in Norse mythology involves a prophesied war where gods and heroes battle until the world is razed. The next generation are left to emerge from the ashes and resurrect their kingdom, repopulating the world once again with gods and humans.

Anselm Kiefer titles his newest exhibition at the White Cube ‘Walhalla’, referring to the Bavarian war monument and the mythological Norse paradise, where those who die in battle are taken. But it is Wagner’s Götterdämmerung to which the show owes its overpowering atmosphere of monstrous apocalypse.

Against this backdrop of mythical destruction and renewal Kiefer incorporates his trademark symbols of post-war desolation with new portents of bleak violence. Upon entry, a corridor with bunker-like walls is lined with hospital beds made from lead; the health and safety notice handed to visitors warning them not to touch the sculptures make the toxic undertones literal – there is no paradise here for Kiefer’s wounded soldiers, even symbols of healing are lethal. A rusty machine gun peeping out from under one of the covers ensures the meaning is unambiguous.

In another, similarly bunker-like room sits a larger rusty bed with crumpled wings sprouting out of either side. A giant rock weighs down the bed, apparently crushing the chimerical creature. The rock could be read as an egg, waiting to hatch on top of its obliterated predecessor. Other rooms feature documents and objects decimated by the effects of war. The most striking of these is a looming nine metre spiral staircase reminiscent of those attached to the side of tenement buildings. Hanging from it are pieces of clothing matted with grit, glass and cement, all a uniform dull grey. The robes evoke slain Valkyries, but trails of film reel root the piece to a more contemporary reality; they are unavoidably evocative of clothes taken from prisoners in concentration camps.

If the sculptures remain resolutely bleak, the paintings offer glimpses of the renewal promised in the Norse myth. The sheer scale of Kiefer’s new paintings are astonishing; these are not comfortably sized ready-to-buy canvases for collectors, but installation art in their own right, made from oil, emulsion, shellac and clay.

Vast expanses of rutted paint, at times so thick it peels off the canvas in fragile shards, pick out blasted, sickly landscapes; Kiefer makes use of grand perspectives to detail miles of stirred up mud. Teetering towers, a recurrent motif across his corpus of work, are out in full force in ‘Bose Blumen’. They belch clouds of noxious brown smoke, but are almost golden in colour: the towers become unhealthy relics of a bombed city. The names of distinguished German artists are etched onto one canvas, reminding us that Kiefer is continuing the tradition of artists envisioning destruction on a catastrophic scale.

In Kiefer’s ‘Rorate Caeli Desuper, iridescent cobalt blue licks the edges of the canvas, forming a hyperreal sky that casts an uncanny light across the wasted ground. In another painting, dabs of red paint serve as flowers growing up through the muck, rare signs of resilience in Kiefer’s vision of a chaotic world. The conflicts between nature, myth and history that play out across Kiefer’s paintings ensure they are the most complex and engaging elements of the show. Kiefer’s sculptures seem less weighed down by the demons of the past, and at times, pieces like ‘Brunhilde’s Rock’, which sees a giant stony mass encased rather blandly in a glass vitrine, lack the bristling tension of the canvases.

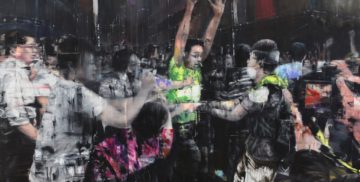

Nevertheless, the central message is imparted powerfully: Kiefer believes apocalypse can happen more than once. The unfriendly hospital beds, mourned heroes and scarred cities are recurrent images in our news cycle; they are symbols of the tragedy of Aleppo as much as they refer to Old Norse stories. This exhibition is not trying to be a prescient emblem of our dark political landscape, but rather seeks to point out that the horrors that ensue when democracy fails have been written in myth for centuries; for Kiefer, this is a story doomed to repeat.